Marine

NAVIGATION

In China compasses have been in use since the Han dynastie (2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE) when they were referred to as 'south-pointers'. However at first these magnets were only used for geomancy much like in the art of Feng Shui. Eventually, during the Sung dynasty (1000 CE) many trading ships were then able to sail as far as Saudi Arabia using compasses for marine navigation. Between 1405 and 1433, Emperor Chu Ti's Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne ruled the entire South Pacific and the Indian Ocean, a territory that ranges from Korea and Japan to the Eastern coast of Africa. At this time Western mariners were still rather ignorant of the navigational use of the magnet. Petrus Perigrinus van Maricourt wrote a first treatise on the magnet itself: "De Magnete" (1269). And though its nautical use was already mentioned in 1187 by the English monk Alexander Neckham, the use onboard only came about around the 13th and 14th century in the Mediterranean Sea. Much later, in 1545, Pedro de Medina (Sevilla 1493-1567) wrote the Spanish standard work "Arte de Navegar" on marine compass navigation. This masterpiece was first translated in Dutch (1580) and was -O Irony- used by Jacob van Heemskerk when the Dutch destroyed the Spanish fleet near Gibraltar in 1607. The drawback was of course Van Heemskerk's own death during this victory.

Magnetic Variation

In the fin-de-siècle of the sixteenth century mariners believed that the North magnetic pole coincided with the North geographic pole. Any suggestion otherwise had been denied by Pedro de Medina. Magnetic observations made by explorers in subsequent decades showed however that these suggestions were true. But it took untill the early nineteenth century, to pinpoint the magnetic north pole somewhere in Arctic Canada (78° N , 104° W). From then on the angle between the true North and the Magnetic North could be precisely corrected for. This correction angle is called Magnetic Variation or declination. It is believed that the Earth's magnetic field is produced by electrical currents that originate in the hot, liquid, outer core of the rotating Earth. The flow of electric currents in this core is continually changing, so the magnetic field produced by those currents also changes. This means that at the surface of the Earth, both the strength and direction of the magnetic field will vary over the years. This gradual change is called the Secular Variation of the magnetic field. Therefore, variation changes not only with the location of a vessel on the earth but also varies in time.

Correcting for Variation

The correction for magnetic variation is shown for your location on your current navigation chart's compass rose. Take for example a variation of 2° 50' E in 1998. In 2000, this variation is estimated to be 2° 54', almost 3° East. This means that if we sail 90° on the chart (your true course), the compass would read 87°.

To convert your true course into a compass course we need first assign a "-" to a Western and a "+" to a Eastern variation. From the following equation you will see that this makes sense:

87° cc + 3° var = 90° tc ,

in which 'cc' and 'tc' stand for 'compas course' and 'true course', respectively.

We can use the same equation to convert a compass course into a true course. If we steered a compass course of 225° for a while, we have to plot this as a true course of 228° in the chart.

Magnetic Deviation

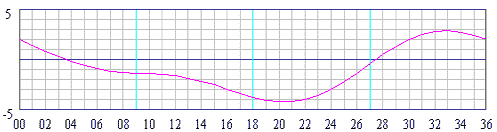

Magnetic deviation is the second correctable error. The deviation error is caused by magnetic forces within your particular boat. Pieces of metal, such as an engine or an anchor, can cause magnetic forces. And also stereo and other electric equipment or wiring , if too close to the compass, introduce large errors in compass heading. Furthermore, the deviation changes with the ship's heading, resulting in a deviation table as shown below. The vertical axis states the correction in degrees West or East, where East is of course positive.

The horizontal axis states the ship's heading in degrees devided by ten. Thus, when you sail a compass course of 220°, the deviation is 4° W.

When a compass is newly installed it often shows larger deviations then this and needs coarse compansation by carefully placing small magnets around the compass. It is the remaining error that is shown in your deviation table.

You can check your table every now and then by placing your boat in the line of a pair of leading lights and turning her 360 degrees.

Correcting for both Deviation and Variation

Converting a compass course into a true course, we can still use our equation but we need to add the correction for deviation:

cc + var + dev = tc

Example 1: The compass course is 330°, the deviation is +3° (table) and the variation is +3° (chart);

330° cc + 3° var + 3° dev = ?° tc

giving a true course of 336° which we can plot in our chart

Example 2: The compass course is 220°, the deviation is -4° (table) and the variation is still +3° (chart).

220° cc + 3° var + -4° dev = ?° tc

giving a true course of 219° which we can plot in our chart.

Converting a true course into a compass course is a little less straight forward, but it is still done with the same equation.

Example 1: The true course from the chart is 305° and the variation is +3° (chart), yet we don't know the deviation;

?° cc + 3° var + ?° dev = 305° tc

Luckily, rewritten this reads:

305° tc - + 3° var = cc + dev = 302°

In plain English: the difference between the true course and the variation (305 - + 3) = 302 should also be the sommation of the compass course and the deviation. So, we can tell our helmsperson to steer 300°, since with a cc of 300° we have a deviation of +2°.

Example 2: The true course from the chart is 150° and we have a Western variation of 7 degrees (-7°). We will use the rewritten equation to get:

150° tc - - 7° var = cc + dev = 157°

From the deviation table we find a compass course of 160° with a deviation of -3°. Voilá!

Magnetic Course

The Magnetic course (mc) is the heading after magnetic variation has been considered, but without compensation for magnetic deviation. This means that we are dealing with the rewritten equation from above:

tc - var = cc + dev = mc. Magnetic courses are used for two reasons. Firstly, the magnetic course is used to convert a true course into a compass course like we saw in the last paragraph. Secondly, on boats with more than one compass more deviation tables are in use; hence only a magnetic or true course is plotted in the chart.

To summarise, we have three types of 'North' (True, Magnetic and Compass north) like we have three types of courses (tc, mc and cc). All these are related by deviation and variation.

Magnetic courses are used for two reasons. Firstly, the magnetic course is used to convert a true course into a compass course like we saw in the last paragraph. Secondly, on boats with more than one compass more deviation tables are in use; hence only a magnetic or true course is plotted in the chart.

To summarise, we have three types of 'North' (True, Magnetic and Compass north) like we have three types of courses (tc, mc and cc). All these are related by deviation and variation.

Overview

Variation: The angle between the magnetic North pole and the geographical North pole. Also called the magnetic declination.

Secular Variation: The chance of magnetic declination in time with respect to both strength and direction of its magnetic field.

West (-) , East (+): Western variations or deviations are designated a negative sign by convention due to the compass card's clock wise direction.

Deviation: The error in compass heading caused by electric magnetic currents and or metal objects.

Deviation Table: A table containing deviations in degrees versus the ship's heading (compass course) in degrees. Usually plotted in a graph.

True Course: Course plotted in the chart i.e. course over the ground or 'course made good'. The course corrected for compass errors.

Compass Course: The course (ship's heading) without the correction for compass errors.

cc + var + dev = tc: This equation shows the connection between the compass course, it's errors and the true course. It can also be read as: tc - var = cc + dev.